“we have met the enemy and they are us”

i’d like to offer three important perspectives on US manufacturing that are seemingly absent in these hyperbolic times as the jingo of trade war drums is intersecting with populist mythology on trade:

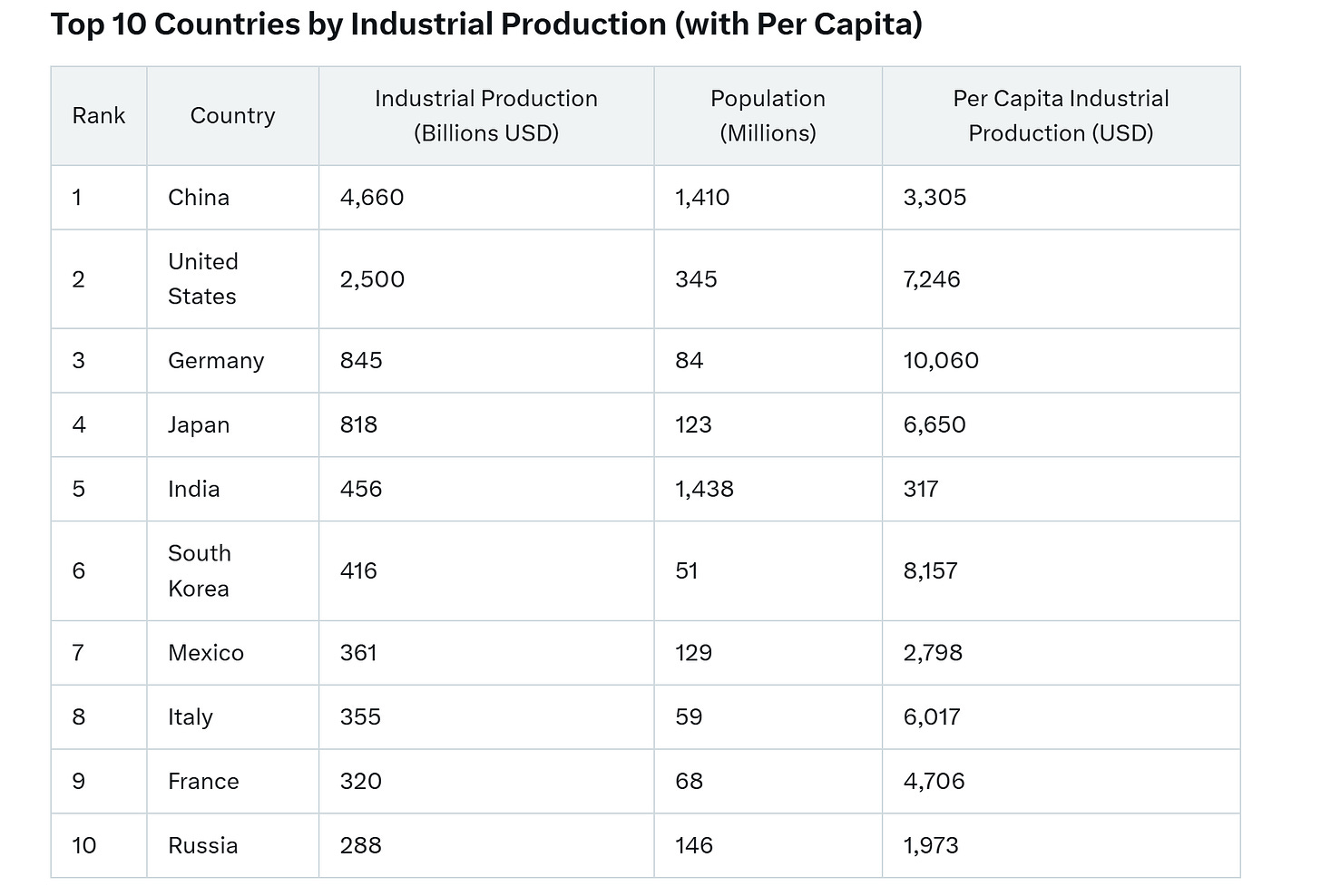

the US is the number two country in the world for industrial output and number 3 (germany) is not even close. we exceed china in per capita industrial output (more than double). the idea that “US manufacturing is gone/has hollowed out” is not factually correct. it simply changed and moved as evolving industries do.

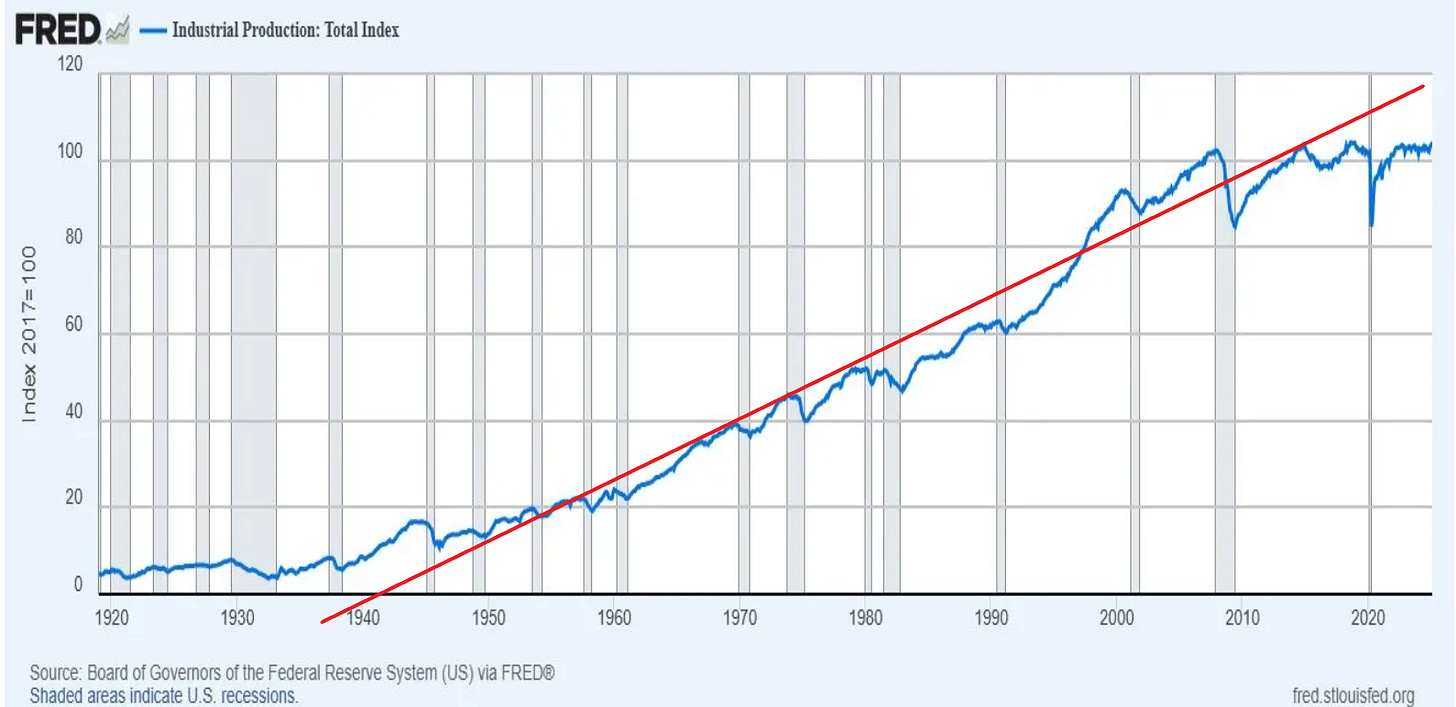

US industrial output today is at or around all time highs in real (inflation adjusted) terms. that said, the long term growth of US industrial output was like a bird hitting a window in 2008 and has not grown since. this change was abrupt and broke a long term tend from the 1940’s to now and there has been no recovery from it. this was not a result of tariffs or foreign action: it was caused domestically with bad energy and labor policy, over support of unions, and horrible litigation risks and hurdles especially driven by the EPA and other federal agencies. this made manufacturing relatively unattractive in the US vs other uses of labor and capital, comparatively disadvantaging it relative to services, intellectual property production, etc. this, not trade barriers has been the prevailing issue limiting US industry.

so long as this issue remains unresolved (and it does), if the world moved to 100% free trade tomorrow with no country limiting US goods and the US limiting no goods from any nation, this would not drive an onshoring of industry to the US. it would drive more industry offshore because that’s how comparative advantage works. manufacturing in the US is too punitive to productivity and capital returns and thus under full free trade, the US would likely specialize more in non-manufactured goods and trade services etc for manufactured goods from abroad where the regulations were not so (relatively) restrictive. the key word here is “relative.” many seem inclined to fixate on absolute differences, but this is not what drives trade or specialization. that’s why trade economics winds up being so non-intuitive to many.

people may not like them, but these are the facts and this is why i am concerned that this trade war really cannot be won in the manner many seem to be advocating and presuming, especially if the win state is defined as “zero or positive bi-lateral trade balances in goods with each of our partners.”

that’s not what free trade would drive.

until we fix the underlying issue with american industrial policy, it likely drives the opposite. and therefore if one’s espoused goal it to “increase US manufacturing” then there is work to be done in order to make free trade serve such a goal.

let’s look at some data:

here’s US industrial production vs others. we’re second place behind china, but still do far more manufacturing than they do per capita. china just has a really large number of people. US industrial production per capita is in line with the hyper industrialized states of korea and japan. only germany is meaningfully higher and that’s collapsing rapidly.

the US is not bereft of manufacturing, it has quite a lot of it.

we’re a global leader and if you take the next 4 nations after us combined, they still do not add up to the US.

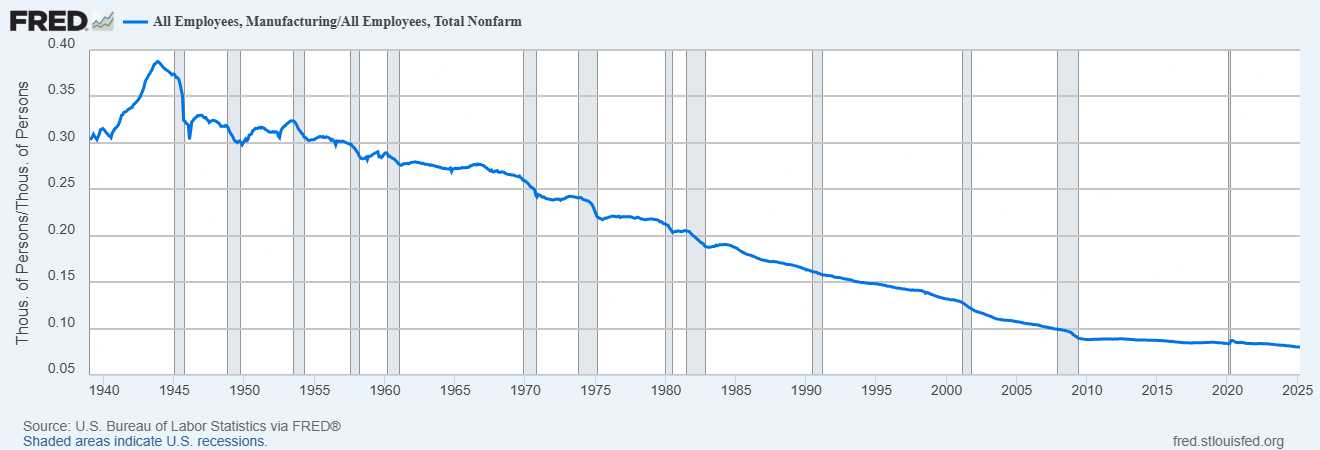

this seems to be the chart that people mistake for output or “industrial decline.”

this shows the % of the US labor force that works in manufacturing.

a far smaller portion of american workers work in manufacturing vs the 1950’s (the early/mid 40’s are a bit of a mess from ww2) but the drop from ~32% to 7-8% is real.

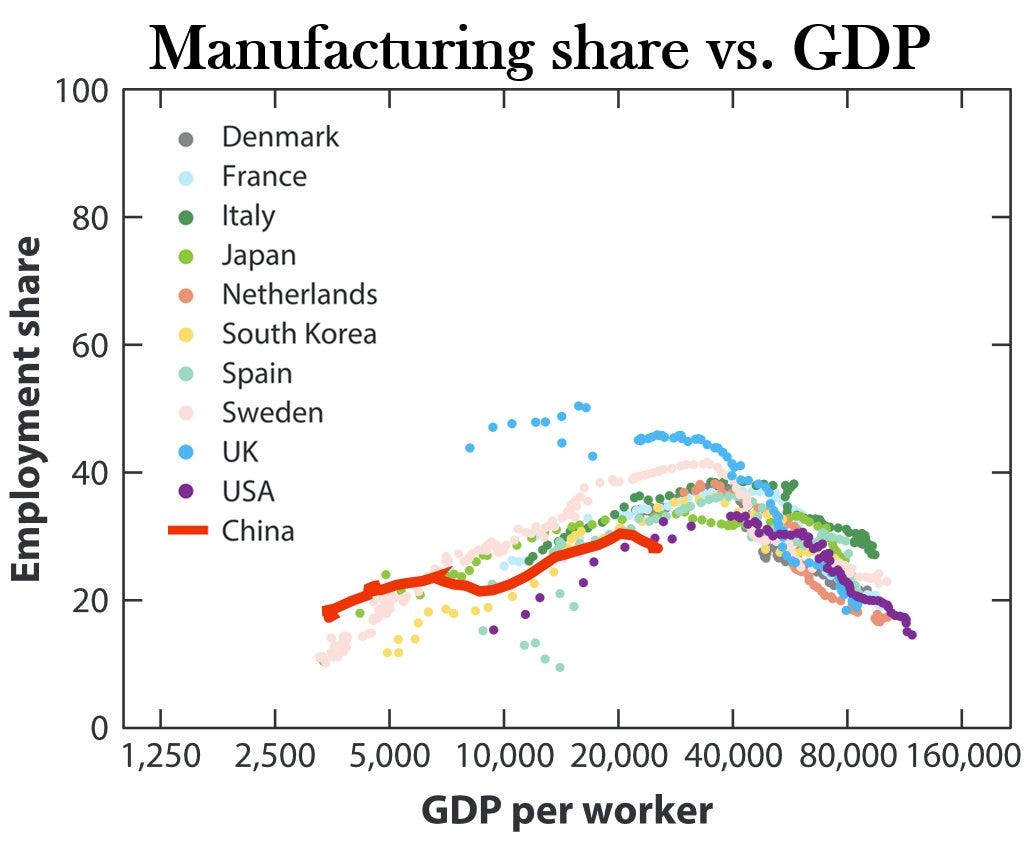

but this has also happened all over the developed world, it is, in fact, a marker of development.

industrial jobs are a part of early wealth creation, but they fade in the later stages because productivity rises too much both for good production and in the value and consumption patterns of other goods, especially services.

again, folks may not like this or find it dissonant with cherished cultural stories/memories, but this trend happens everywhere. it’s a part of the nature of economic development, not “factory jobs being stolen.”

to cross $30-40k in per capita GDP, you need to start allocating labor to more productive uses and using manufacturing labor more productively (through automation).

from 1970 to 2012 the % of workers in germany who work in manufacturing halved.

this is just a thing that happens when your economy enters the next stage. it’s the path to getting rich.

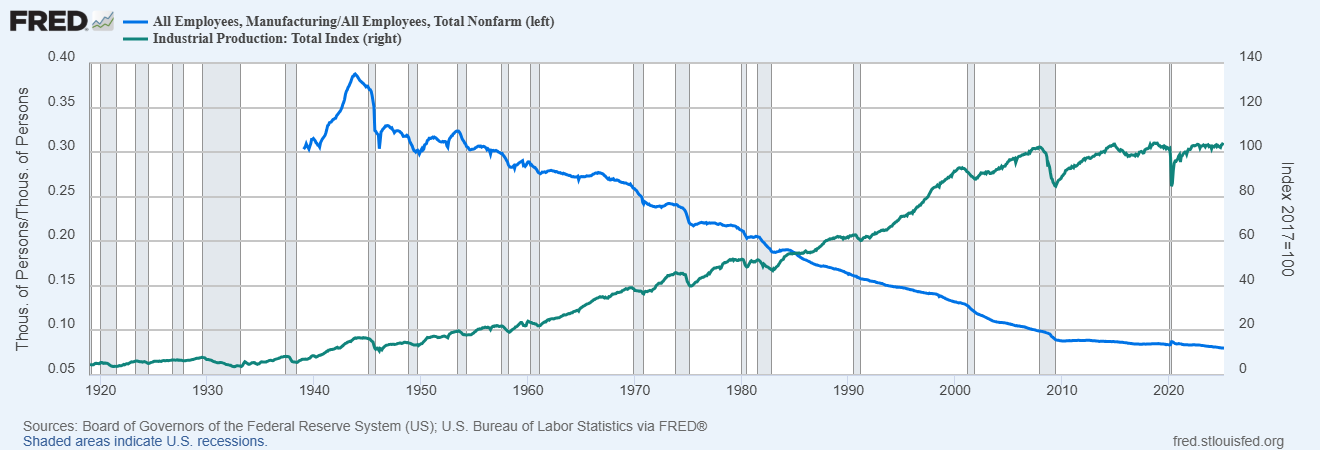

this shows up clearly if we show industrial output next to % of workers in manufacturing.

from 1945 to 2008 we had a massive rise in output (12 to 102, a nearly nine-fold rise) but the % of the labor force in this space plummeted. it actually dropped in actual workers, peaking in 1979 at 19.5 million and dropping to 11.5 million in 2009 from which it has risen to 12.7 today.

many seek to cast this as “bad” but is it? this is productivity, fewer people making more output. it’s what makes things affordable, plentiful, and varied. we could increase construction employment by banning shovels and making everyone dig with their hands and lots of people would get jobs. what do you think those jobs would pay? not much. productivity would be terrible. how much would a house wind up costing? a lot. it would take forever to build. productivity is prosperity. no one wants to go back to all shoes being hand made. (you can buy them BTW, they’re lovely. they also cost $1,400 a pair.)

97-99% of people used to work in agriculture. now it’s 1-2% and we have an obesity problem unimaginable when almost everyone had to work on food production because one person with a combine can harvest more wheat in a day than a human with a scythe can in a year. (note that this is also the answer to the “so why did wages stop rising as fast as productivity?” objection: it’s because productivity became driven near entirely by automation and mechanization and the guy who bought you the combine to drive needs to get a return on it and you’re sharing the extra productivity with them and generally both benefit from it.)

so let’s go back to 2008: so what happened?

why did we never recover from 2008 and regain the (admittedly arbitrary) trend line i added here?

how did this just drop dead? we grew ~3.5% a year for 60+ years, then went to basically zero over the next 16.

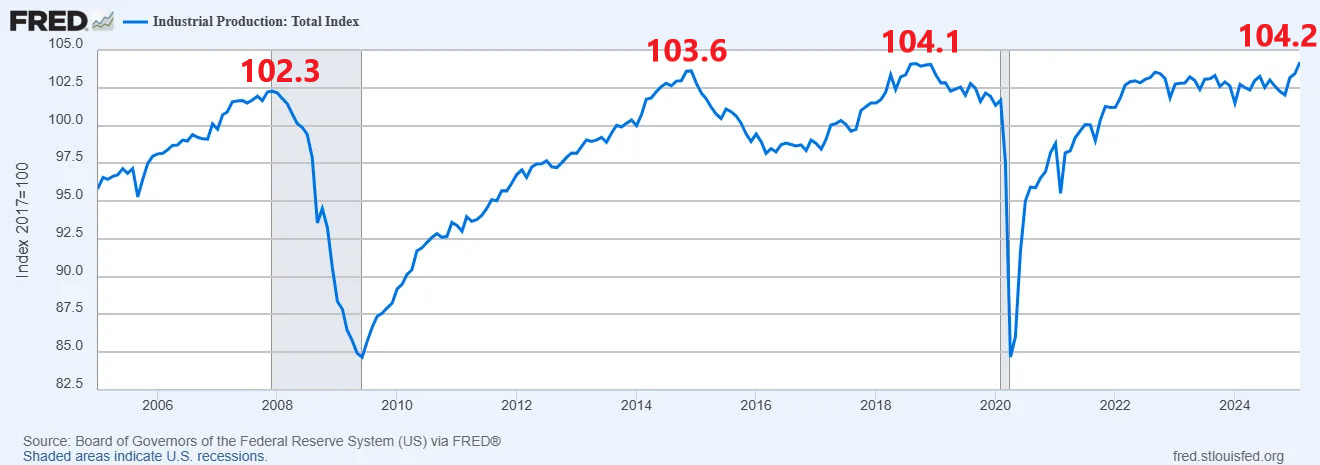

let’s zoom in. as can be readily seen, this is not growth, it’s a cardiac rhythm. some sort of upper boundary condition has been imposed and growth just plain stopped.

this new inability/disincentive to expand industrial output not caused by tariffs or changes in foreign markets.

the origin of the 16 year malaise was barry obama and his team of eco/labor dictators. this was not done to us, it was an own goal from which we have never recovered.

the great enemy of US industry is not our trade partners, it’s the US government.

it’s really important to keep that in mind.

why did US industry stop growing? because it was made uncompetitive, not just with the rest of the world (which actually matters less than most think) but uncompetitive with other uses of labor and capital here in the US.

the notoriously misnamed “affordable care act” mandated health care for all employees at firms of over 50 people. the workforce investment act trained people away from manufacturing. unions were given more power and killed the companies they held sway over.

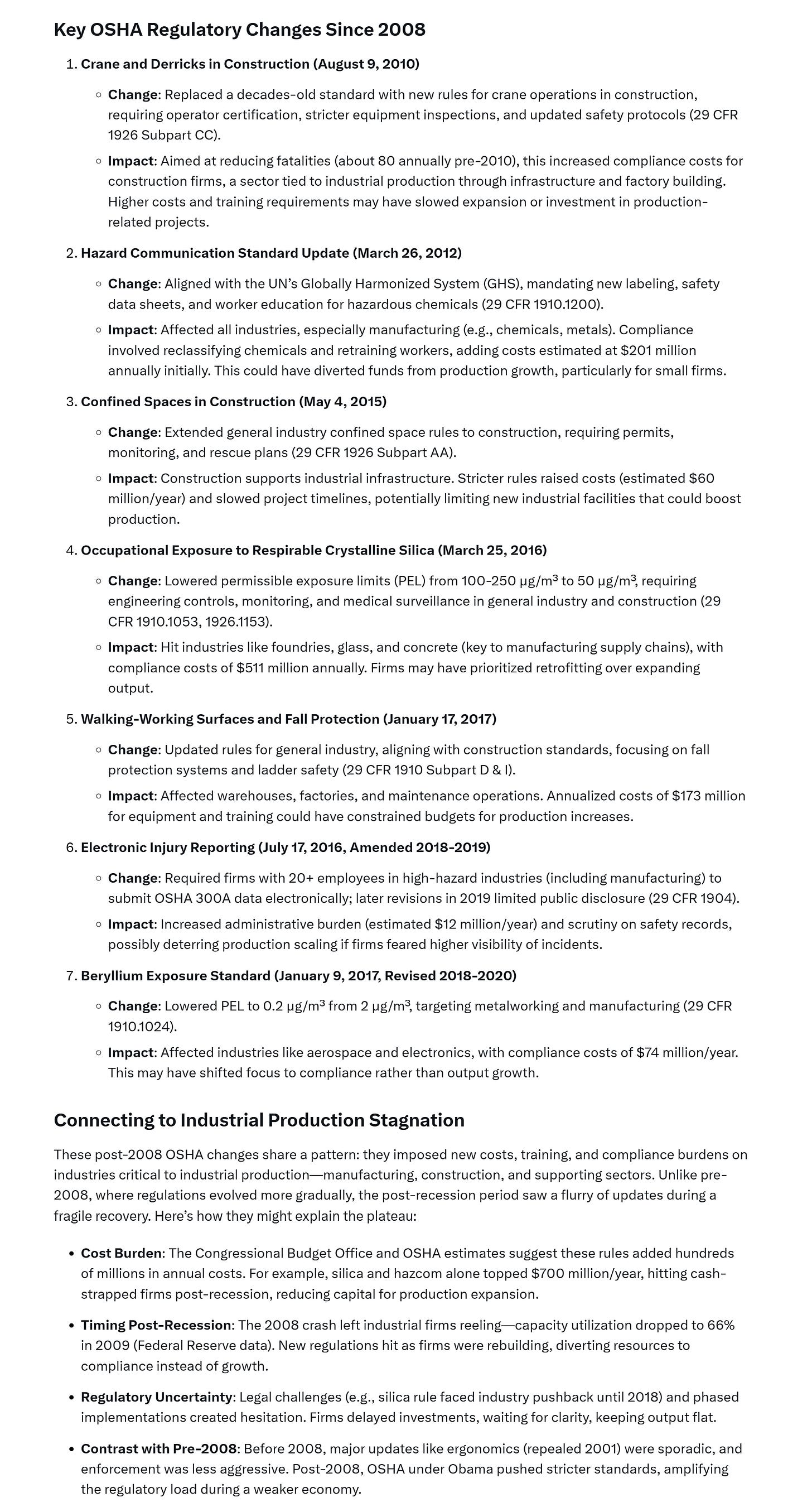

but the real killer were the regulators. OSHA became gravel in the gears and the EPA became outright glue.

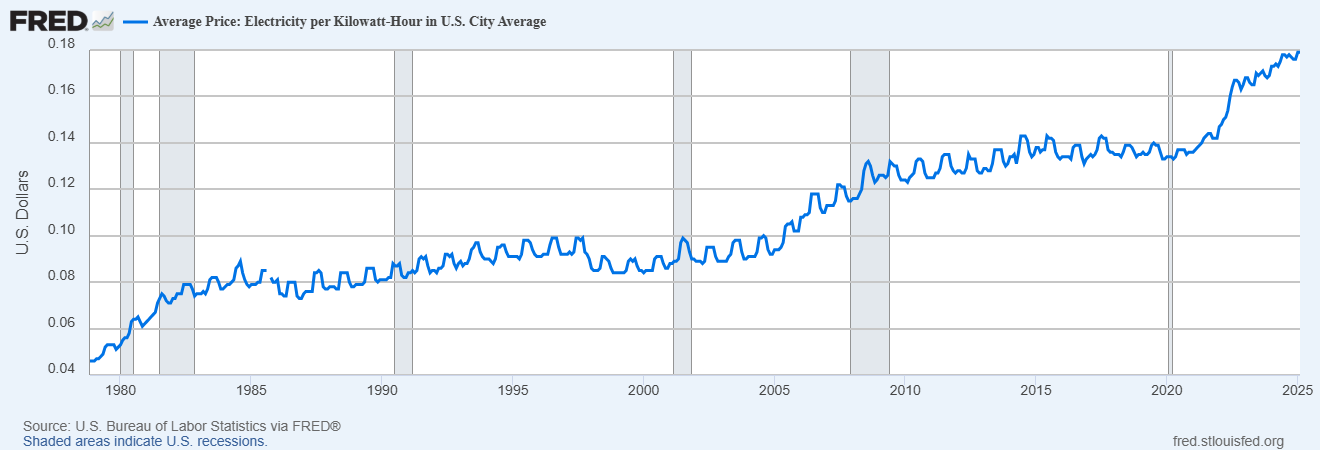

the clean air act amendments made opening a factory much harder. ditto powerplants. some of this predated BO, but he really turned the screws. electricity prices rose 50% and never looked back. this is not good for manufacturing.

but the absolute backbreaker became green grift and permitting. the “clean power plan” froze investment and constant threats of brining it back did likewise. uncertainty is bad for business that involves long term planning and long periods to recoup capital (as factories do). the “waters of the US” rule made permitting a horror. it just went on and on. it got to the point where just getting approval to build could take years, for complex projects decades. i remember watching them try to expand the san francico airport. every truck had to drive 3 mph and have someone walk in front of it to make sure they did not run over any garter snakes. (yes, really)

how is anyone supposed to build and run an industrial base under these conditions?

worse, with so much power vested in unaccountable agencies whose actions and priorities change every presidential election, how can anyone plan? if it takes years to build and years more to get a return and you cannot have any idea what the regulatory environment will look like in 4 years, who wants to put capital at risk?

this was the truly massive damage of BO, a move to far more muscular regulators having huge, unpredictable effects and it never goes away because very election is a new spin of the wheel with new problems and restrictions.

sure, lots of the EU is competing for similarly stupid prizes from similarly stupid gameplay, but much of the world is not (and at least the EU is less variable) but who has more foolish and restrictive rules is not actually the major driver: the major driver is specialization to drive advantage from trade.

this arranges not around absolute advantage but around comparative advantage. it’s not about “can the US make a car more cheaply than china” it’s “can the US make a car with relatively fewer resources relative to other things that it could be making with those resources than china can with regard to the other things it could be making?”

it’s ultimate manifestation is “what is the more efficient use of your resources?”

this is the part of trade people seem to misunderstand.

let me try some very basic ricardo:

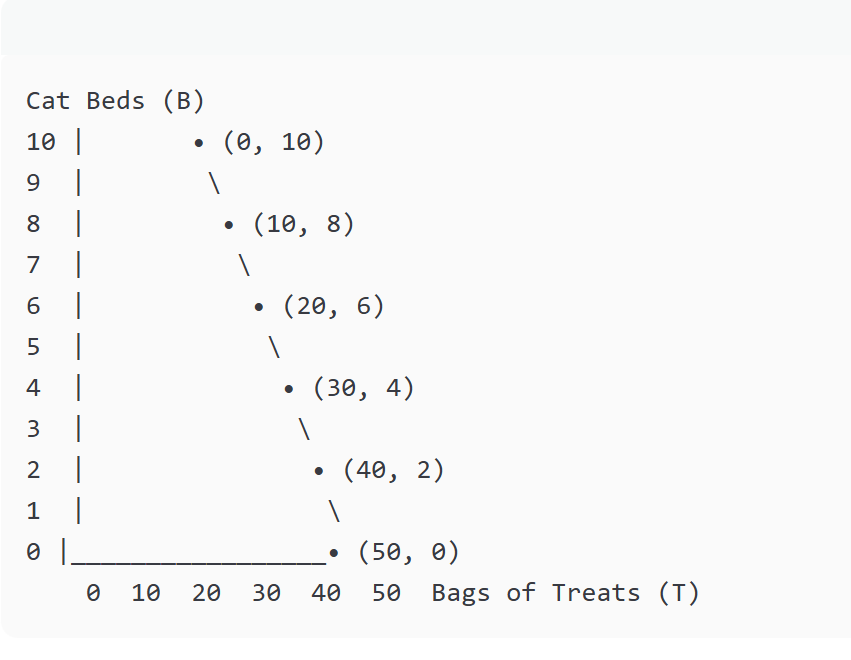

if gatoland has 100 units of labor and can make a bag of treats for 2 units of labor or a cat bed for 10 units of labor, this is the production possibility frontier (PPF) under autarky (no trade)

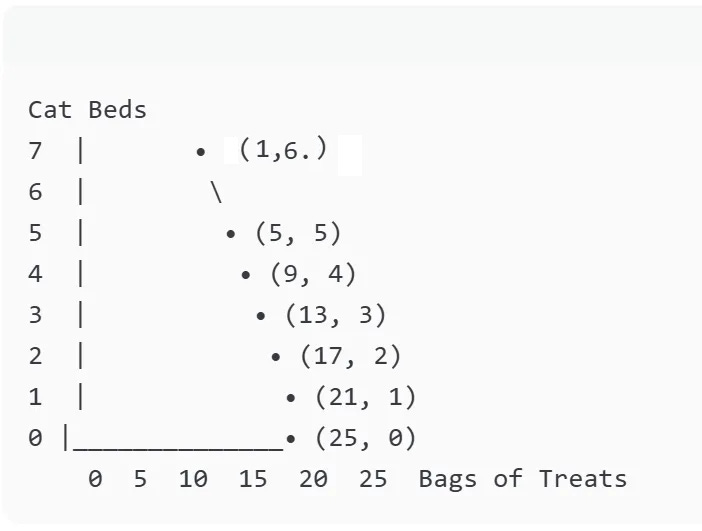

if perrostan has 100 units of labor and can make a bag of treats for 4 units or a cat bed for 16 units, they are obviously worse at making both things than the gatos. (sorry, doggins, life isn’t fair)

their PPF looks like this:

if left alone and unable to trade

let’s say the cats make 20 treats and 6 beds.

let’s say the dogs make 9 treats and 4 beds.

(these are indifference points, but let’s assume the beds are a number both sides need and treats are just “nice to have.”)

gatos are better producers of all goods, but there is still benefit to both sides from trade. in gatoland, the opportunity cost to make one bed is 5 units of treats. for the dogs, it’s only 4. so the dogs should specialize in making beds.

if instead the dogs make 6 beds (more than they want) and only one treat

and the cats then make 4 beds (fewer than they want) but 30 treats, now they can trade.

the cats get 2 beds from the dogs and again have 6, the dogs again have 4.

the dogs get 9 treats from the cats and now have 10, one more than before.

the cats still have 21 treats left, one more than before.

everyone is better off.

that is how specialization around comparative advantage works. its not about whether the cats are better at making treats or beds than dogs, it’s about the relative ability of cats to make treats vs their ability to make beds compared to the dog’s relative ability to make treats vs beds.

this is the key insight needed to see how maximization from trade occurs and optimizes.

it’s one of the least intuitive issues in economics and a class even a lot of econ majors struggle with.

you can see that the flipside does not work. if the dogs made all treats, that would be 25. the cats would then make all beds and get 10. this leaves everyone worse off because comparative advantage has not been followed. the dogs trade 20 treats to the cats (leaving the cats where they were before) and get 4 beds in return (feline indifference point under autarky) but only have 5 treats left instead of 9.

specialization against comparative advantage has made the world overall poorer.

it is not the absolute difference in ability to make things that drives this, it’s the relative value of other uses of scarce inputs (opportunity cost). you have to specialize to take advance of it. trying to go the other way turns a 2 treat gain into a 4 treat loss. a positive sum process becomes a negative sum one.

and for progress and well being, positive sum is where it’s at.

gatoland is better at making everyhting, but specializing and trading with the doggies is better still.

specialization around comparative advantage is vital to welfare maximization.

what drives this sort of “comparative advantage” is exactly things like “regulation” or “resource costs.”

this is why, given how unattractive manufacturing had been made relative to other things in the US, i say that even if we had 100% free unfettered trade tomorrow, the US would likely offshore more manufacturing. we have comparative advantage in “not manufacturing” because our government has made manifesting so difficult and the time horizons on which it pays too unpredictable.

we develop most of the high tech bleeding edge equipment to make semiconductors here. but no one build a fab. even the CHIPS act loaded with subsidy was a clownshow of failure.

the EPA is impossible, the hiring rules and DEI a disaster, the costs out of line, and electricity too expensive and fabs DRINK electricity. a mega-fab can use 8-9000 GWh of electricity a year, about the same as a city of several hundred thousand. this is a bit more than the full annual output of typical large nuclear reactor. this business is hyper competitive and always moving. a new mega fab takes 2-3 years to plan and build under optimal conditions. this can easily stretch if your regulators are difficult. they cost $20-25 billion. you seriously want to take this on if regulators 3 years from now might suddenly hold you up for some new law or permit or jack you up for new fees or demands on wastes etc?

nope. you’ll go invest in something else or build your fab someplace where the regulators are less mercurial. that’s a determinant on comparative advantage vs other uses of capital in the US.

if we want to get US industry growing again (we can debate the desirability of that, but let’s take it as a given) then we need to make running industry in the US reasonable again. we need to make it plausible to build nuclear plants, refineries, smelters, forges, semi-fabs, and 400 other things.

we need to change the relative game.

the path to this is not tariffs that will impose large deadweight losses or free trade that will make us de-industrialize further because we’re the (richer) cats in the ricardo example and would get richer still by making more treats to trade for beds.

the path to this is de-regulation in a real, durable, permanent fashion.

it’s limiting these agencies not just now, but forever.

it’s creating an environment where investing capital in industry makes sense on timescales and risk weighted return relative to other uses of capital (like developing the intellectual property which constitutes most of the value in the chain and then having the chips or drugs or cell phones made offshore).

we can argue about if we actually want this industry back (do you really want the low value add job of assembling an iphone?) but if you do for whatever reason (security, self-sufficiency, whatever) then the only positive sum path to doing this has to start with regulation in the US.

that’s where we broke this and that’s what needs to be fixed to make the machine function as it once did.

So well said! You are 100% right that it has been the strangulation of manufacturing businesses by regulators and politicians who want to solve every perceived problem, no matter how small, no matter the cost and no matter the impact on business and jobs. Remember the clown show Obama and Biden administrations’ favorite response to lost jobs: “go learn and code.” Both administrations were run by people who never created a job and never built anything. What we need is a roll back of all the unnecessary job crushing laws, rules, and regulations passed since Barack Obama His Own Self was elected.

Obama's "new normal." Certainly the most destructive president in modern times, perhaps in all time.